Since we all have a little bit more free time on our hands right now, it might be a great time to truly understand the relationship between your calorie intake and your weight. Over 70% of the adult population in America is clinically considered either overweight or obese. This occurs as a result of two things, we are moving less and eating more, especially while on quarantine.

Regardless of what anyone will ever try to sell you, weight management always boils down to calories. Calories are measurable units of energy that we can either consume (through food) or burn. Every human has a total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), that is defined as the amount of energy (calories) spent, on average, in a typical day. This is commonly referred to as one’s metabolism. TDEE is composed of three different types of calorie expenditure:

Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR): This usually accounts for about 70% of your TDEE and consists of all the things that keep you alive while at rest. This means it is the minimum energy expended to sustain body functions such as circulation, respiration, and temperature regulation.

Thermic effect of food (TEF): This is the amount of energy used as a result of digesting food for storage and use. This makes up roughly 10% of your calorie intake (1).

Thermic Effect of Exercise (TEE): All the additional energy used beyond your RMR and TEF from typical movement, to your weight training or cardio, makes up the last portion. This will be about 20% of your TDEE.

There is a fourth category that is often simply grouped in with RMR.

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): Calories burned fidgeting, changing posture, etc. This is usually subconscious.

Trainers and weight loss apps such as myfitnesspal come up with the number of calories they recommend you eat by using formulas that take your weight, age, and gender into consideration.

We then take this number and multiply it by whats called an Activity Factor to figure out your current TDEE. Activity Factors range from 1.2 to 1.9 and are listed below:

Sedentary: 1.2 (little or no exercise)

Lightly active: 1.375 (light exercise/sports one to three days per week)

Moderately active: 1.55 (moderate exercise/sports six to seven days per week)

Very active: 1.725(hard exercise/sports six to seven days per week)

Extra active: 1.9 (very hard exercise/sports and a physical job)

Again, these are estimates, but are still a great starting point. They help us account for the fact that even if another individual is the same height and weight as you, and has the same goals, the end result might be completely different due to their activity level. If they have a job that forces them to be on their feet all day, while you have to remain seated, they will burn more calories throughout their day (even before they exercise) than you do and this will have to be worked into their program.

It is always better to underestimate than overestimate when calculating this. You also want to figure this number out based off of your typical activity level, not your newly started program.

(If you’re curious what your RMR and TDEE are, Click Here to skip to the calculator at the bottom of this page!)

These formulas provide amazing baselines for starting your program, but every variation of the formula has its own risk of error or inaccuracy. Since every human is different, as your program progresses, your result may need to be modified based off the progress you are making. Therefore it should be viewed as more reference point, than a finalized setting.

Summary: What’s commonly referred to as your metabolism is made up by the number of calories your body burns 1) to keep you alive, 2) to digest food, and 3) through movement (whether it be intentional exercise or subconscious fidgeting). We calculate how many calories to assign you by taking those factors into consideration and then applying additional formulas relevant to your goals. We will go over some specific examples later in the article.

Excess Energy Storage = Fat

In its simplest terms, if you burn more calories a day than you take in, you will lose weight. Likewise, if you consume more calories a day than you expend, you will gain weight (2,3).

Unfortunately, we usually don't realize how many calories we actually take in. And on top of that, most jobs and hobbies keep us stationary and burn next to zero calories (desk jobs, driving, Netflix, scrolling through instagram, etc). Our goal is to safely reduce your calories by choosing foods high in nutrients but low in calories, and increase your calorie expenditure through exercise. This will allow us to decrease your body fat percentage and increase your lean body mass (LBM).

The body was created/evolved to survive. Storing fat is simply that, your body setting itself up for survival. If you consumed more calories than you technically need, you now have an extra supply of energy your body is going to stockpile. That way if a day comes in which your body doesn't have enough energy to fuel its TDEE, it can tap into those stores to survive and function as it would normally.

How many calories do I need to burn in order to lose a pound of fat?

Now that you understand how we calculate your RMR and TDEE, you need to understand how we modify these numbers to help you get where you want to be.

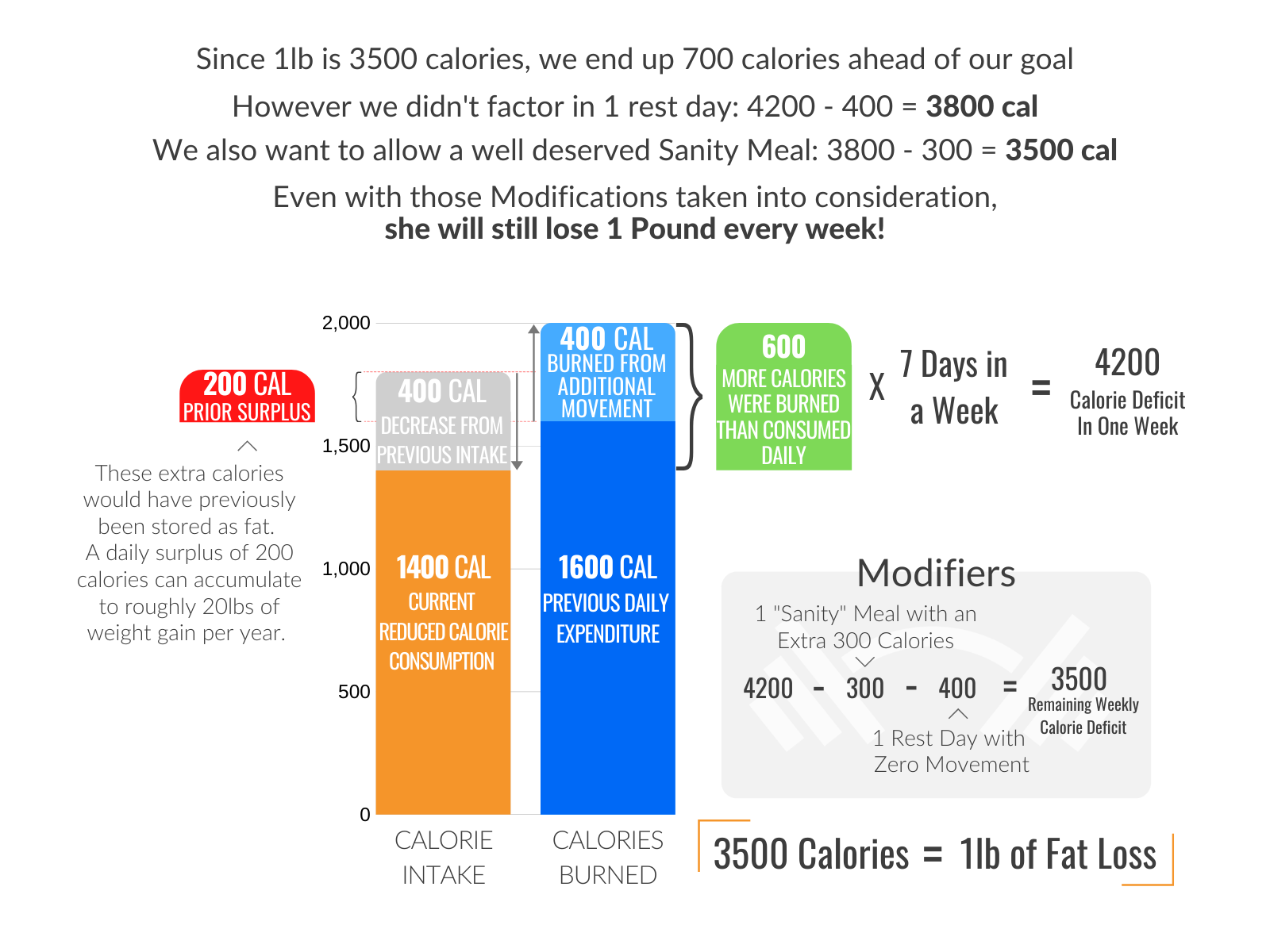

The simple version we usually teach: One pound of fat storage consists of roughly 3500 calories (4). If you maintain a 500 calorie deficit for 7 consecutive days (500 x 7 = 3500), you will lose 1lb of fat. If you increase this to a 1000 calorie deficit, you will then lose 2 lbs of fat. When you maintain this deficit through a combination of eating healthier or moving more, your body will start to tap into that stored energy, decreasing your weight.

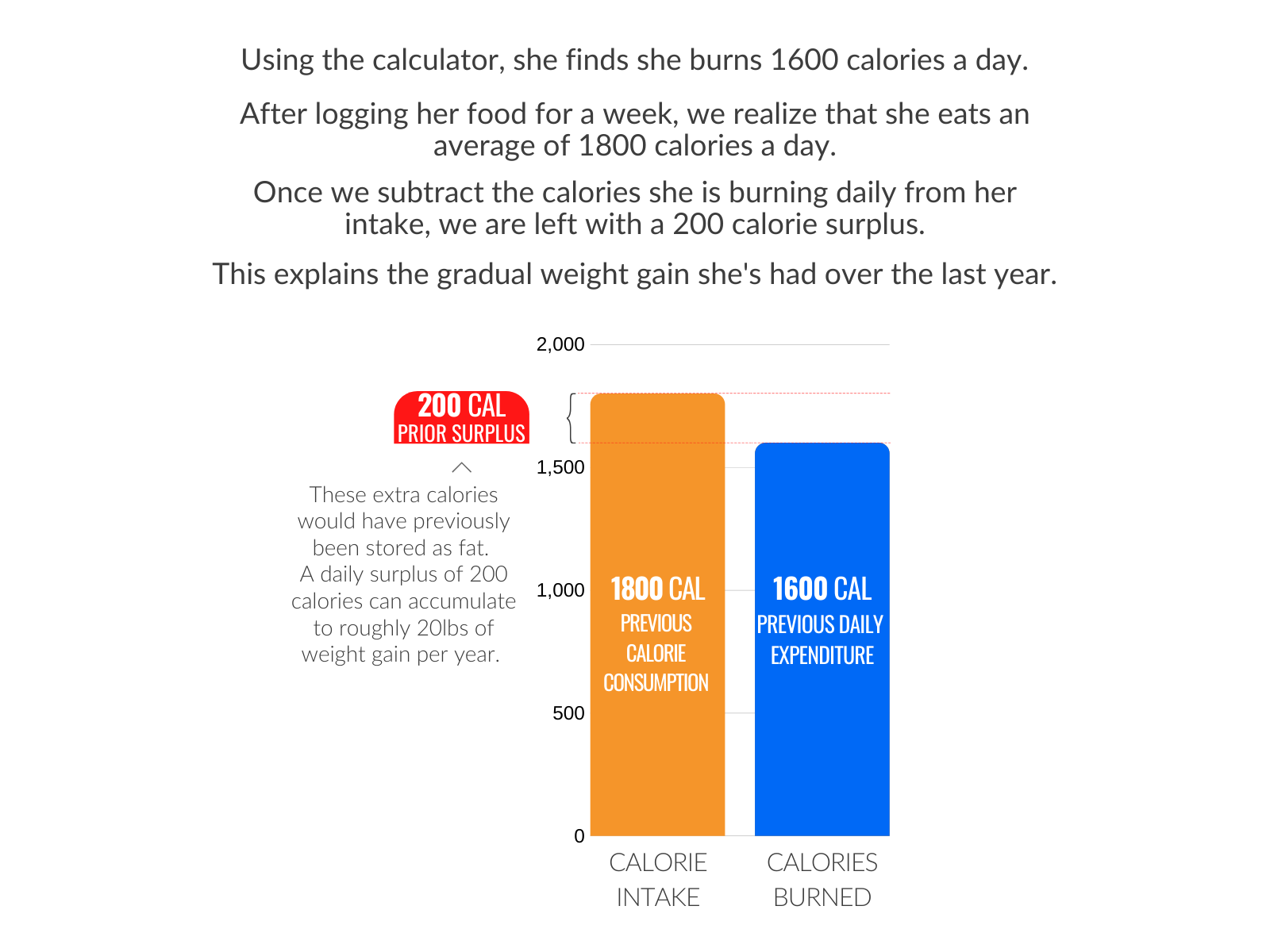

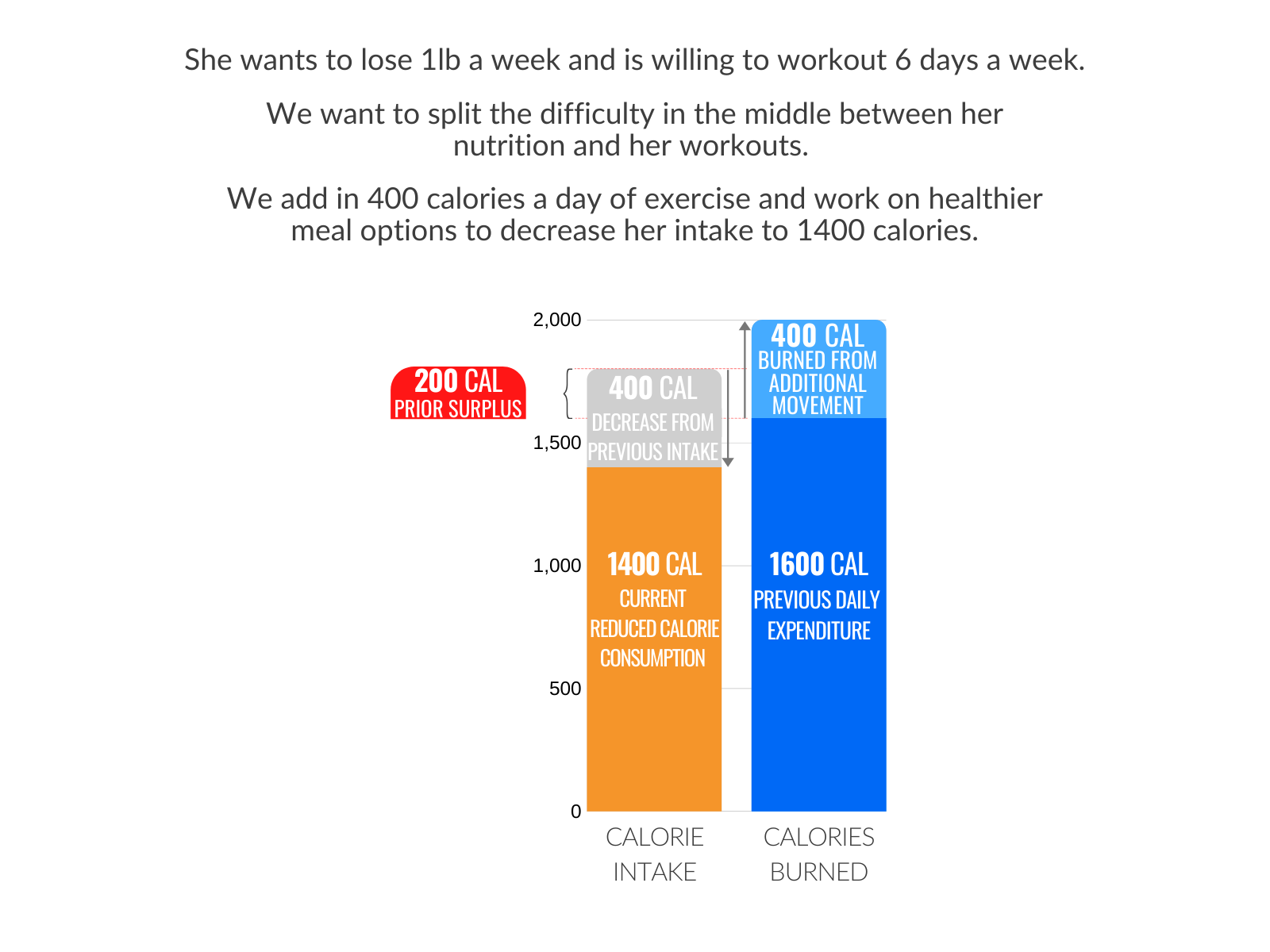

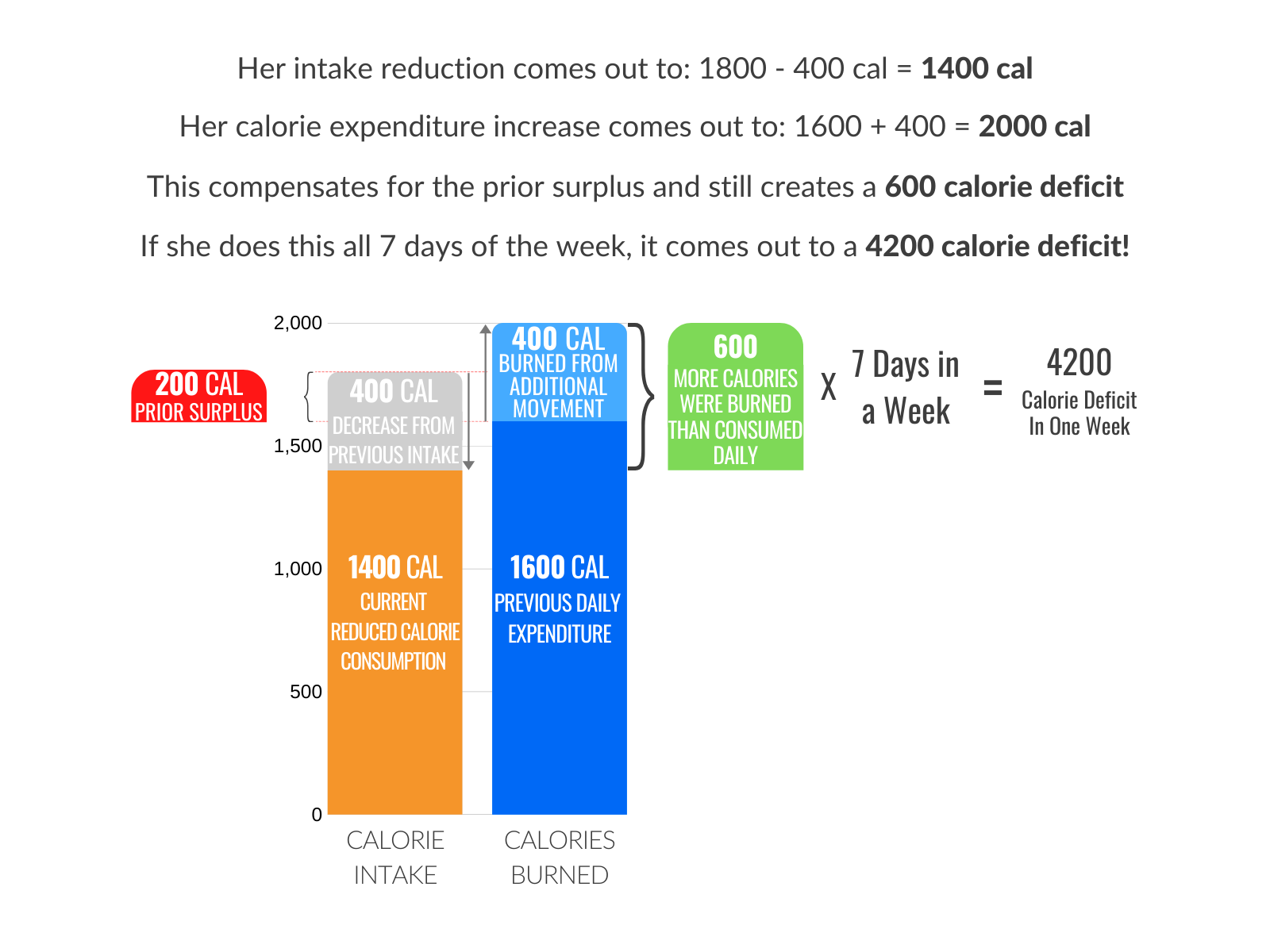

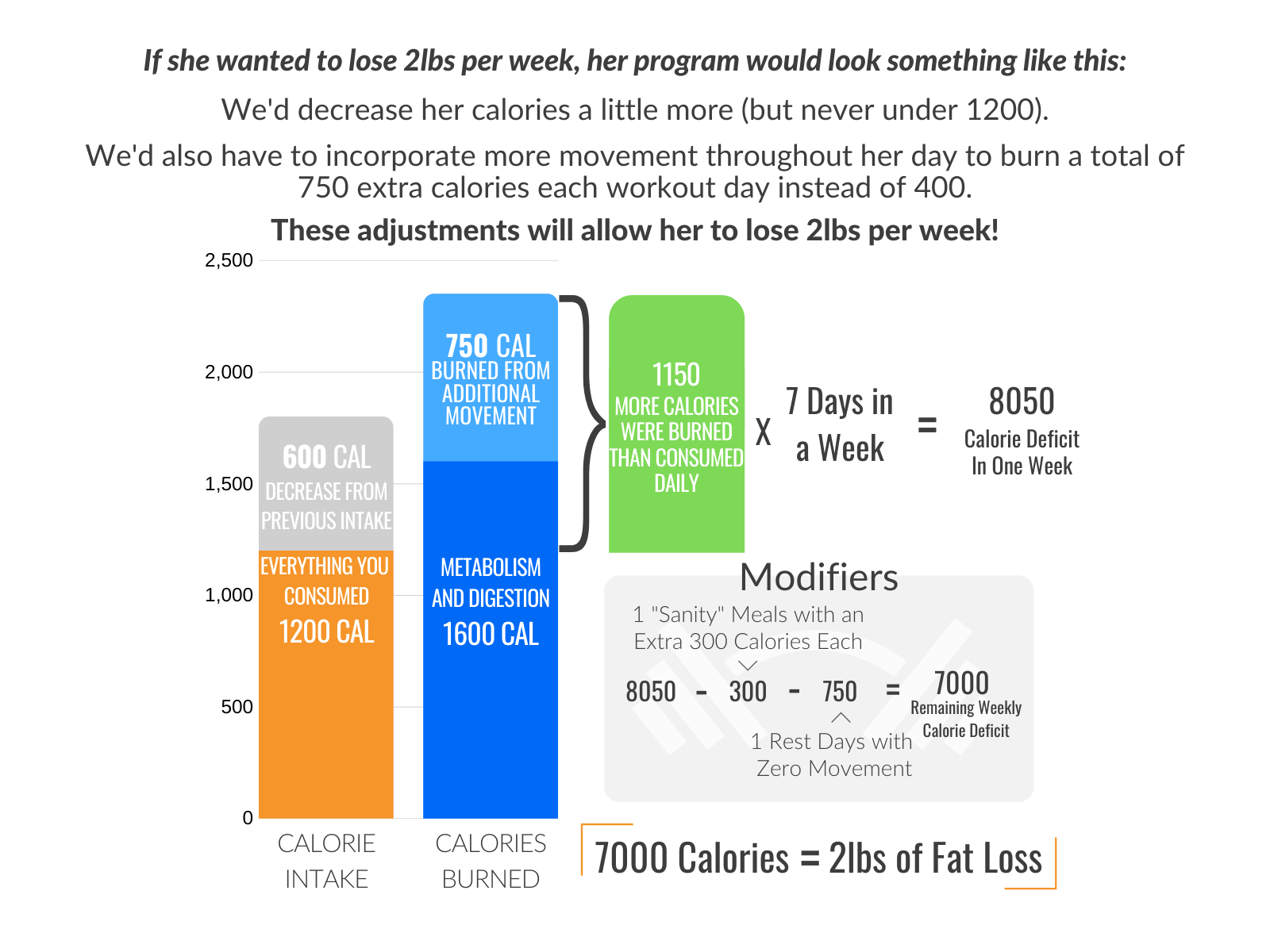

The image below follows the simplified format of how we would determine how to modify your lifestyle to start you on your journey.

Now, this deficit that we decide on, gets created using your TDEE as a baseline. You can go ahead and use the calculator right below this to figure out what your TDEE is and the amount of calories you would need to consume in order to lose 1 or 2lbs per week!

Updated Reality: This is still fairly accurate when it comes to short term weight loss, but it can set unrealistic expectations for long term goals since it doesn’t take into consideration the body's response to the changes in body composition and diet (5). The body is amazing in that it’ll adapt to whatever stress we put it under.

Want to run longer or get stronger? Then practice putting your body under that type of stress. But when you reduce calorie intake, your body responds to that demand by becoming more efficient. It does the same amount of work, but uses fewer calories than before. This is both remarkable and incredibly frustrating at the same time (6).

For every pound that you lose, it then takes 5.8 fewer calories per day to maintain your body mass (9). So if you lose 25lbs, your maintenance point would then be (25 x 5.8) roughly 150 calories lower than it previously was.

This is what the term “starvation mode” is referring to in most situations. However, its technical term is "adaptive thermogenesis” and is a natural physiological response (7). As soon as you reduce your calorie intake to a point where you are losing weight, your body panics and the brain starts taking steps to prevent this. By either making you hungrier, so you make up that deficit, or by decreasing the number of calories that you burn. The decrease in calories out (calories burned) involves a reduction in both conscious and subconscious movement, and a major change in the function of the nervous system and various hormones (7,8).

“Ok I don’t want to have to eat less… How can I prevent this from happening?”

This is one of the reasons it is so important to implement resistance training as you lose weight. An increase in muscle mass can offset the decrease in metabolism from dropping weight (10).

Eat protein, which can reduce appetite and cravings, as well as boost metabolism by 80-100 calories per day (11).

Enjoy yourself a little! “Refeed” days where you eat slightly above maintenance can help temporarily boost the hormones that go down with weight loss (12).

Because of these factors, for weight loss, we recommend between 1-2lbs per week (50-100lbs per year) in order to create a sustainable and healthy lifestyle that will result in you looking and feeling the way you want to beyond just the next few months.

(If your goal is to gain weight, we will do the opposite, we will implement an intentional excess of calories beyond your TDEE by anywhere from 200-500 calories in order to prompt weight gain and an excess of nutrients for muscle synthesis. We will consistently modify this to make sure the highest percentage of weight that is gained is muscle, and not simply additional body fat.

Once you are at your desired weight, our goal is to match your calorie intake with your TDEE and consistently increase the quality of your intake. Creating a healthier you inside and out.)

Summary: Your body will store unused calories as fat but this can be tapped into through dieting or exercise. Initially, one pound of stored fat is roughly 3500 calories but as you lose weight and eat healthier, your body adapts by burning fewer calories. Exercise helps make sure your calorie expenditure doesn’t decrease rapidly. If you want to gain weight, start out with a minimal calorie surplus and reassess monthly.

Heres an example of how all that information works together to create a program

Our example client will be:

a 31 year old female

She is 5’ 4” and 140lbs.

She has a desk job and doesn’t currently exercise, so she would classify as sedentary.

She’s been slowly gaining weight and wants to put a stop to it.

Follow the pictures below to see how the program would evolve:

If you need some help developing a program that works for you, fill out the form below and a myFIT trainer will reach out to give you a helping hand.

Sources:

1). Groff JL, Gropper SS, Hunt SM. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing, 1995.

2). Faires VM. Thermodynamics. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1967.

3). Jensen MD. Diet effects on fatty acid metabolism in lean and obese humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67(3 Suppl):531S-4S

4). WISHNOFSKY M. Caloric equivalents of gained or lost weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1958 Sep-Oct;6(5):542-6

5). Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, Chow CC, Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lancet. 2011 Aug 27;378(9793):826-37

6). 1: Rosenbaum M, Vandenborne K, Goldsmith R, Simoneau JA, Heymsfield S, Joanisse DR, Hirsch J, Murphy E, Matthews D, Segal KR, Leibel RL. Effects of experimental weight perturbation on skeletal muscle work efficiency in human subjects. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003 Jul;285(1):R183-92. Epub 2003 Feb 27. PubMed PMID: 12609816.

7) 1: Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010 Oct;34 Suppl 1:S47-55. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.184. Review. PubMed PMID: 20935667; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3673773.

8). 1: Arone LJ, Mackintosh R, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Hirsch J. Autonomic nervous system activity in weight gain and weight loss. Am J Physiol. 1995 Jul;269(1 Pt 2):R222-5. PubMed PMID: 7631897.

9) 1: Schwartz A, Doucet E. Relative changes in resting energy expenditure during weight loss: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2010 Jul;11(7):531-47. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00654.x. Epub 2009 Sep 17. Review. Erratum in: Obes Rev. 2011 Oct;12(10):884. PubMed PMID: 19761507.

10) 1: Hunter GR, Byrne NM, Sirikul B, Fernández JR, Zuckerman PA, Darnell BE, Gower BA. Resistance training conserves fat-free mass and resting energy expenditure following weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008 May;16(5):1045-51. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.38. Epub 2008 Mar 6. PubMed PMID: 18356845.

11) 1: Veldhorst MA, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Westerterp KR. Gluconeogenesis and energy expenditure after a high-protein, carbohydrate-free diet. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Sep;90(3):519-26. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27834. Epub 2009 Jul 29. PubMed PMID: 19640952.

12) 1: Poehlman ET, Tremblay A, Fontaine E, Després JP, Nadeau A, Dussault J, Bouchard C. Genotype dependency of the thermic effect of a meal and associated hormonal changes following short-term overfeeding. Metabolism. 1986 Jan;35(1):30-6. PubMed PMID: 3510362.